Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners

Contemporary Concepts and Treatments Part 1

This is an 8 minute audio recording of this blog

Let me paint a picture.

You are a female runner who usually runs on flat ground and competed in three marathons per year for the last three years before you had your first baby. The baby is now a year old and you wish to get back into running and compete in a half-marathon later in the year.

The prospect of running and competing again is exciting and one weekend you decide to push it by running 20k (12.4 miles) from your usual 10k (6.2 miles) practice runs. To get more out of your run, you also decided to try out a hill trail near you. You assume that you will be able to manage the trail.

However, by the time you come down the hill after managing the uneven course, you feel a sharp, piercing pain on the outer aspect of your knee which is now getting aggravated on activities like climbing down the stairs and squats.

The pain tends to come on at about 3km (1.5 miles) while running every time, your knee starts feeling tighter and tighter as you run and eventually it forces you to stop. You have tried stretching and rolling over foam rollers of all shapes and sizes but nothing seems to help.

Does any part of this sound familiar to you?

Chances are that you might have developed Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS). NO it’s not the name of a rock band! Though your IT band does feel ‘Hard as a Rock’ (Hat tip to AC/DC!)

ITBS is the second leading cause of pain in the running population and it is the second most common overuse injury (patello-femoral pain being the first which is more likely to cause pain on the front of the knee) (1)

ITBS is the second leading cause of pain in the running population and it is the second most common overuse injury

Unfortunately, it seems that women are twice at risk of developing this condition than men. However, it is not specific just to runners and is the most common repetitive strain injury in female soccer, cyclists, field hockey and military personnels. (2) This condition is also seen in weekend hikers, trail runners and post surgery.

Even though this is one of the most common conditions to affect female athletes, the exact source of what causes it still remains unclear.

Frustratingly, all this confusion has led to a lack of effective treatment approaches. You can’t treat it if you don’t understand it!

The aim of this blog post is to explore the various factors that contribute to this condition and the various treatment approaches used to help give you a better idea of how to tackle it more efficiently.

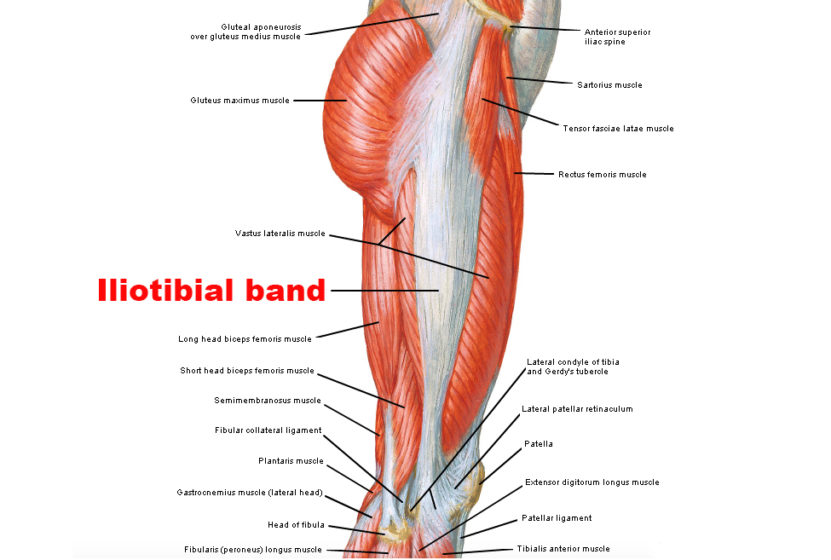

ANATOMY OF THE ILIOTIBIAL BAND (THE NAME ITSELF IS MISLEADING!)

The IT band has been one of those tissues in the body which has functionally mystified clinicians for a long time. Structurally, it’s not a distinct band but by classification rather: a thickening of your fascia. It is part muscle, part ligament and part tendon and covers your thigh like a stocking or a tight wrap.

A considerable part of your Gluteus Maximus muscle inserts into the ITB along with the tensor fascia late (TFL). The ITB has attachments at the pelvis and the knee, and inserts along the length of your thigh bone. It is attached, rather strongly, to the outside of your knee all the way to the shinbone. (3)

These attachments are indicative of the intricate relationship between the ITB, the hip and knee complex, as well as to how it is designed to provide stability and act as a spring to absorb forces during activities.

WELCOME TO ITB PAIN – WHERE CAUSES ARE MADE UP & FRICTION DOESN’T MATTER!

Because of these deep attachments of the ITB and the firm anchors, it does not snap or roll or slip over the side of the knee. So there’s no friction between the ITB and the bone as was earlier thought to produce pain and inflammation.

Because of these deep attachments of the ITB and the firm anchors, it does not snap or roll or slip over the side of the knee

This is important information, as runners usually have the fear that they are increasing the friction by continuing to run and they are going to harm their knees.

As a physical therapist, I’m aware of the words I use in sessions while educating my patients about this injury and making sure that they understand that it’s a training load injury. In my opinion, telling them that they should never run again would be counterproductive and could lead to more fear of movement and negative clinical outcomes.

This friction-theory led to the adoption of stretching being the commonly recommended treatment for ITB pain (an example of how misunderstanding of anatomy can lead to ineffective treatment approaches).

The current evidence states that the IT band cannot be stretched and we don’t want it stretched either. We need it to be tight and strong, like a ‘spring,’ to stabilize the hip and the knee during running. (2)

SO, WHAT COULD BE CAUSING ALL THAT PAIN?

It was earlier thought that the friction resulted in the inflammation of an anatomical bursa (a small fluid-filled sac) between the tendon and the bone. Current evidence does not support this theory and the presence of an anatomical bursa. (3)

There’s a claim that it’s more of a compression injury than a friction injury. There’s a layer of fat which contains a lot of nerves present between the ITB and the lower portion of the thigh bone (femur) which maintains joint cavity spaces. This adipose tissue gets compressed as the knee bends past 30 degrees (functional ‘impingement zone’) which occurs usually early in the mid-stance phase of running. (Right after foot strike) (2,3)

CLINICAL PRESENTATION- WHO GETS IT?

Classically, a runner will complain of an ache or sharp pain on the outer aspect of the knee, which usually gets aggravated by downhill running. The athlete can also complain of a feeling that their knee might snap. It usually presents itself when runners suddenly increase their training volume (it’s an overload injury) and run on downhill trails or cambered courses. ITB pain has a tendency to come on about the same distance into the activity. (2,3)

Certain biomechanical factors, like weak hip muscles, can lead to the dropping of the pelvis on the opposite side which in turns leading to the hip turning in and the knees collapsing inwards (dynamic knee valgus) while running. This can lead to narrow step width, especially while running downhill, and can put a runner at risk of developing ITBS.

Increase in ITB strain (change in strain on the ITB/ Change in time) has also been reported when running with a narrow step width (2). Although it has been suggested that runners with hip muscle weakness and decreased ability to eccentrically control the hip during downhill running, can lead to the development of ITBS but based on current findings this might not be the sole cause.

It might be the other way around with the ITB pain causing the hip muscle weakness. Improper footwear, lack of recovery, leg length inequalities, weakness in the thigh muscles can also lead to development of ITBS.

These are important considerations, as too often, the devil isn’t, in fact, in the details, but in the complexity of the person struggling with these symptoms. In part 2 of this piece, I will discuss evidence-based treatments for this injury.

For supplementary material please follow these free resources below:

- Exercises for Runners with Knee Pain

- Great exercises for female athletes with knee pain

- Return to Run Program

REFERENCES

- Charles D, Rodgers C. A LITERATURE REVIEW AND CLINICAL COMMENTARY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME IN RUNNERS. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2020 May;15(3):460-470. PMID: 32566382; PMCID: PMC7296998.

- Geisler PR. Iliotibial Band Pathology: Synthesizing the Available Evidence for Clinical Progress. J Athl Train. 2020 Dec 22. doi: 10.4085/JAT0548-19. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33351908.

- Brukner et al., 2016. Brukner & Khan’s clinical sports medicine. 5th ed. New South Wales: McGraw-Hill Education Australia, p.809.

- Willy RW, Meira EP. Current Concepts in Biomechanical Interventions for Patellofemoral Pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11:877-890.